Procopius

Procopius | |

|---|---|

| Born | c. AD 500 Caesarea Maritima, Palaestina Prima, Eastern Roman Empire |

| Died | c. AD 565 |

| Occupation | Legal adviser, political commentator |

| Subject | Secular history |

| Notable works |

|

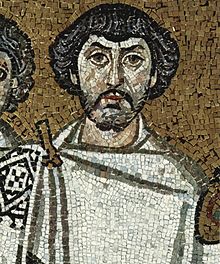

Procopius of Caesarea (‹See Tfd›Greek: Προκόπιος ὁ Καισαρεύς Prokópios ho Kaisareús; Latin: Procopius Caesariensis; c. 500–565) was a prominent late antique Greek scholar and historian from Caesarea Maritima.[1][2] Accompanying the Roman general Belisarius in Emperor Justinian's wars, Procopius became the principal Roman historian of the 6th century, writing the History of the Wars, the Buildings, and the Secret History.

Early life

[edit]Apart from his own writings, the main source for Procopius's life is an entry in the Suda,[3] a Byzantine Greek encyclopaedia written sometime after 975 which discusses his early life. He was a native of Caesarea in the province of Palaestina Prima.[4] He would have received a conventional upper class education in the Greek classics and rhetoric,[5] perhaps at the famous school at Gaza.[6] He may have attended law school, possibly at Berytus (present-day Beirut) or Constantinople (now Istanbul),[7][a] and became a lawyer (rhetor).[3] He evidently knew Latin, as was natural for a man with legal training.[b]

Career

[edit]In 527, the first year of the reign of the emperor Justinian I, he became the legal adviser (adsessor) for Belisarius, a general whom Justinian made his chief military commander in a great attempt to restore control over the lost western provinces of the empire.[c]

Procopius was with Belisarius on the eastern front until the latter was defeated at the Battle of Callinicum in 531[11] and recalled to Constantinople.[12] Procopius witnessed the Nika riots of January, 532, which Belisarius and his fellow general Mundus repressed with a massacre in the Hippodrome there.[13] In 533, he accompanied Belisarius on his victorious expedition against the Vandal kingdom in North Africa, took part in the capture of Carthage, and remained in Africa with Belisarius's successor Solomon the Eunuch when Belisarius returned east to the capital. Procopius recorded a few of the extreme weather events of 535–536, although these were presented as a backdrop to Byzantine military activities, such as a mutiny in and around Carthage.[14][d] He rejoined Belisarius for his campaign against the Ostrogothic kingdom in Italy and experienced the Gothic siege of Rome that lasted a year and nine days, ending in mid-March 538. He witnessed Belisarius's entry into the Gothic capital, Ravenna, in 540. Both the Wars[15] and the Secret History suggest that his relationship with Belisarius cooled thereafter. When Belisarius was sent back to Italy in 544 to cope with a renewal of the war with the Goths, now led by the able king Totila, Procopius appears to have no longer been on Belisarius's staff.[citation needed]

As magister militum, Belisarius was an "illustrious man" (Latin: vir illustris; ‹See Tfd›Greek: ἰλλούστριος, illoústrios); being his adsessor, Procopius must therefore have had at least the rank of a "visible man" (vir spectabilis). He thus belonged to the mid-ranking group of the senatorial order (ordo senatorius). However, the Suda, which is usually well-informed in such matters, also describes Procopius himself as one of the illustres. Should this information be correct, Procopius would have had a seat in Constantinople's senate, which was restricted to the illustres under Justinian. He also wrote that under Justinian's reign in 560, a major Christian church dedicated to the Virgin Mary was built on the site of the Temple Mount.[16][unreliable source?]

Death

[edit]It is not certain when Procopius died. Many historians—including Howard-Johnson, Cameron, and Geoffrey Greatrex—date his death to 554, but there was an urban prefect of Constantinople (praefectus urbi Constantinopolitanae) who was called Procopius in 562. In that year, Belisarius was implicated in a conspiracy and was brought before this urban prefect.[citation needed]

In fact, some scholars[who?] have argued that Procopius died at least a few years after 565 as he unequivocally states in the beginning of his Secret History that he planned to publish it after the death of Justinian for fear he would be tortured and killed by the emperor (or even by general Belisarius) if the emperor (or the general) learned about what Procopius wrote (his scathing criticism of the emperor, of his wife, of Belisarius, of the general's wife, Antonina: calling the former "demons in human form" and the latter incompetent and treacherous) in this later history. However, most scholars believe that the Secret History was written in 550 and remained unpublished during Procopius' lifetime.[citation needed]

Writings

[edit]

The writings of Procopius are the primary source of information for the rule of the emperor Justinian I. Procopius was the author of a history in eight books on the wars prosecuted by Justinian, a panegyric on the emperor's public works projects throughout the empire, and a book known as the Secret History that claims to report the scandals that Procopius could not include in his officially sanctioned history for fear of angering the emperor, his wife, Belisarius, and the general's wife. Consequently publication was delayed until all of them were dead to avoid retaliation.

History of the Wars

[edit]Procopius's Wars or History of the Wars (‹See Tfd›Greek: Ὑπὲρ τῶν Πολέμων Λόγοι, Hypèr tōn Polémon Lógoi, "Words on the Wars"; Latin: De Bellis, "On the Wars") is his most important work, although less well known than the Secret History.[17] The first seven books seem to have been largely completed by 545 and may have been published as a set. They were, however, updated to mid-century before publication, with the latest mentioned event occurring in early 551. The eighth and final book brought the history to 553.

The first two books—often known as The Persian War (Latin: De Bello Persico)—deal with the conflict between the Romans and Sassanid Persia in Mesopotamia, Syria, Armenia, Lazica, and Iberia (present-day Georgia).[18] It details the campaigns of the Sassanid shah Kavadh I, the 532 'Nika' revolt, the war by Kavadh's successor Khosrau I in 540, his destruction of Antioch and deportation of its inhabitants to Mesopotamia, and the great plague that devastated the empire from 542. The Persian War also covers the early career of Procopius's patron Belisarius in some detail.

The Wars’ next two books—known as The Vandal War or Vandalic War (Latin: De Bello Vandalico)—cover Belisarius's successful campaign against the Vandal kingdom that had occupied Rome's provinces in northwest Africa for the last century.

The final four books—known as The Gothic War (Latin: De Bello Gothico)—cover the Italian campaigns by Belisarius and others against the Ostrogoths. Procopius includes accounts of the 1st and 2nd sieges of Naples and the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd sieges of Rome. He also includes an account of the rise of the Franks (see Arborychoi). The last book describes the eunuch Narses's successful conclusion of the Italian campaign and includes some coverage of campaigns along the empire's eastern borders as well.

The Wars proved influential on later Byzantine historiography.[19] In the 570s Agathias wrote Histories, a continuation of Procopius's work in a similar style.

Secret History

[edit]

Procopius's now famous Anecdota, also known as Secret History (‹See Tfd›Greek: Ἀπόκρυφη Ἱστορία, Apókryphe Historía; Latin: Historia Arcana), was discovered centuries later at the Vatican Library in Rome[20] and published in Lyon by Niccolò Alamanni in 1623. Its existence was already known from the Suda, which referred to it as Procopius's "unpublished works" containing "comedy" and "invective" of Justinian, Theodora, Belisarius and Antonina. The Secret History covers roughly the same years as the first seven books of The History of the Wars and appears to have been written after they were published. Current consensus generally dates it to 550, or less commonly 558.

In the eyes of many scholars, the Secret History reveals an author who had become deeply disillusioned with Emperor Justinian, his wife Theodora, the general Belisarius, and his wife Antonina. The work claims to expose the secret springs of their public actions, as well as the private lives of the emperor and his entourage. Justinian is portrayed as cruel, venal, prodigal, and incompetent. In one passage, it is even claimed that he was possessed by demonic spirits or was himself a demon:

And some of those who have been with Justinian at the palace late at night, men who were pure of spirit, have thought they saw a strange demoniac form taking his place. One man said that the Emperor suddenly rose from his throne and walked about, and indeed he was never wont to remain sitting for long, and immediately Justinian's head vanished, while the rest of his body seemed to ebb and flow; whereat the beholder stood aghast and fearful, wondering if his eyes were deceiving him. But presently he perceived the vanished head filling out and joining the body again as strangely as it had left it.[21]

Similarly, the Theodora of the Secret History is a garish portrait of vulgarity and insatiable lust juxtaposed with cold-blooded self-interest, shrewishness, and envious and fearful mean-spiritedness. Among the more titillating (and dubious) revelations in the Secret History is Procopius's account of Theodora's thespian accomplishments:

Often, even in the theatre, in the sight of all the people, she removed her costume and stood nude in their midst, except for a girdle about the groin: not that she was abashed at revealing that, too, to the audience, but because there was a law against appearing altogether naked on the stage, without at least this much of a fig-leaf. Covered thus with a ribbon, she would sink down to the stage floor and recline on her back. Slaves to whom the duty was entrusted would then scatter grains of barley from above into the calyx of this passion flower, whence geese, trained for the purpose, would next pick the grains one by one with their bills and eat.[22]

Furthermore, Secret History portrays Belisarius as a weak man completely emasculated by his wife, Antonina, who is portrayed in very similar terms to Theodora. They are both said to be former actresses and close friends. Procopius claimed Antonina worked as an agent for Theodora against Belisarius, and had an ongoing affair with Belisarius' godson, Theodosius.

Justinian and Theodora are portrayed as the antithesis of "good" rulers, with each representing the opposite side of emotional spectrum. Justinian was of "approachable and kindly" temperament, even while ordering property confiscations or people's destruction. Conversely, Theodora was described as irrational and driven by her anger, often by minor affronts.[e]

Interpretations

[edit]Procopius is believed to be aligned with many of the senatorial ranks that disagreed with Justinian and Theodora's tax policies and property confiscations (Secret History 12.12-14).[24][25]

On the other hand, it has been argued that Procopius prepared the Secret History as an exaggerated document out of fear that a conspiracy might overthrow Justinian's regime, which—as a kind of court historian—might be reckoned to include him. The unpublished manuscript would then have been a kind of insurance, which could be offered to the new ruler as a way to avoid execution or exile after the coup. If this hypothesis were correct, the Secret History would not be proof that Procopius hated Justinian or Theodora.[26]

Researcher Anthony Kaldellis suggests that the Secret History is a tale of the dangers of "the rule of women". Procopius's perspective was that women's vices vanquished men's virtuous leadership.[f] For Procopius, it was not that women could not lead an empire, but only women demonstrating masculine virtues were suitable as leaders. Rather than Theodora's true possession of strength, it was Justinian's lack of it that created the impression of strength in her.[27] According to researcher Averil Cameron, the definition of "feminine" behavior in the sixth century would be described as "intriguing" and "interfering". She argues Procopius's intent in including her speech during the Nika riots in the Wars may be to demonstrate that Theodora does not stay in her appropriate role.[28] At his core, Procopius wanted to preserve the social order of men standing over women.[g]

In Averil Cameron's view, Procopius is more aptly described as a reporter rather than a historian, providing a black-and-white description of events, rather than a deeper analysis of the causes and motives.[30] Cameron argues that his intense political focus and exaggeration of the imperial couple's vices prevent a balanced and holistic perspective, resulting in a portrayal of Justinian and Theodora as caricatural villains.[h][31]

The Buildings

[edit]

The Buildings (‹See Tfd›Greek: Περὶ Κτισμάτων, Perì Ktismáton; Latin: De Aedificiis, "On Buildings") is a panegyric on Justinian's public works projects throughout the empire.[32] The first book may date to before the collapse of the first dome of Hagia Sophia in 557, but some scholars think that it is possible that the work postdates the building of the bridge over the Sangarius in the late 550s.[33] Historians consider Buildings to be an incomplete work due to evidence of the surviving version being a draft with two possible redactions.[32][34]

Buildings was likely written at Justinian's behest, and it is doubtful that its sentiments expressed are sincere. It tells us nothing further about Belisarius, and it takes a sharply different attitude towards Justinian. He is presented as an idealised Christian emperor who built churches for the glory of God and defenses for the safety of his subjects. He is depicted showing particular concern for the water supply, building new aqueducts and restoring those that had fallen into disuse. Theodora, who was dead when this panegyric was written, is mentioned only briefly, but Procopius's praise of her beauty is fulsome.

Due to the panegyrical nature of Procopius's Buildings, historians have discovered several discrepancies between claims made by Procopius and accounts in other primary sources. A prime example is Procopius's starting the reign of Justinian in 518, which was actually the start of the reign of his uncle and predecessor Justin I. By treating the uncle's reign as part of his nephew's, Procopius was able to credit Justinian with buildings erected or begun under Justin's administration. Such works include renovation of the walls of Edessa after its 525 flood and consecration of several churches in the region. Similarly, Procopius falsely credits Justinian for the extensive refortification of the cities of Tomis and Histria in Scythia Minor. This had actually been carried out under Anastasius I, who reigned before Justin.[35]

Style

[edit]Procopius belongs to the school of late antique historians who continued the traditions of the Second Sophistic. They wrote in Attic Greek. Their models were Herodotus, Polybius and in particular Thucydides. Their subject matter was secular history. They avoided vocabulary unknown to Attic Greek and inserted an explanation when they had to use contemporary words. Thus Procopius includes glosses of monks ("the most temperate of Christians") and churches (as equivalent to a "temple" or "shrine"), since monasticism was unknown to the ancient Athenians and their ekklesía had been a popular assembly.[36]

The secular historians eschewed the history of the Christian church. Ecclesiastical history was left to a separate genre after Eusebius. However, Cameron has argued convincingly that Procopius's works reflect the tensions between the classical and Christian models of history in 6th-century Constantinople. This is supported by Whitby's analysis of Procopius's depiction of the capital and its cathedral in comparison to contemporary pagan panegyrics.[37] Procopius can be seen as depicting Justinian as essentially God's vicegerent, making the case for buildings being a primarily religious panegyric.[38] Procopius indicates that he planned to write an ecclesiastical history himself[39] and, if he had, he would probably have followed the rules of that genre. As far as known, however, such an ecclesiastical history was never written.

Some historians have criticized Propocius's description of some barbarians, for example, he dehumanized the unfamiliar Moors as "not even properly human". This was however, inline with Byzantine ethnographic practice in late antiquity.[40]

Legacy

[edit]A number of historical novels based on Procopius's works (along with other sources) have been written. Count Belisarius was written by poet and novelist Robert Graves in 1938. Procopius himself appears as a minor character in Felix Dahn's A Struggle for Rome and in L. Sprague de Camp's alternate history novel Lest Darkness Fall. The novel's main character, archaeologist Martin Padway, derives most of his knowledge of historical events from the Secret History.[41]

The narrator in Herman Melville's novel Moby-Dick cites Procopius's description of a captured sea monster as evidence of the narrative's feasibility.[42]

List of selected works

[edit]- J. Haury, ed. (1962–1964) [1905]. Procopii Caesariensis opera omnia (in Greek). Revised by G. Wirth. Leipzig: Teubner.

4 volumes

- Dewing, H. B., ed. (1914–1940). Procopius. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, Massachusetts and London: Harvard University Press and Hutchinson. Seven volumes, Greek text and English translation.

- Downey, G.; Dewing, Henry B., eds. (1940). Buildings of Justinian. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- Procopius: The Secret History. Penguin Classics. Translated by Williamson, G. A. Revised by Peter Sarris. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. 2007 [1966]. ISBN 978-0140455281.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) English translation of the Anecdota. - Prokopios: The Secret History. Translated by Anthony Kaldellis. Indianapolis: Hackett. 2010. ISBN 978-1603841801.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ For an alternative reading of Procopius as a trained engineer, see Howard-Johnson.[8]

- ^ Procopius uses and translates a number of Latin words in his Wars. Börm suggests a possible acquaintance with Vergil and Sallust.[9]

- ^ Procopius speaks of becoming Belisarius's advisor (symboulos) in that year.[10]

- ^ Before modern times, European and Mediterranean historians, as far as weather is concerned, typically recorded only the extreme or major weather events for a year or a multi-year period, preferring to focus on the human activities of policy makers and warriors instead.

- ^ For example, Procopius describes two separate incidents where she uses the judicial system to publicly accuse men of having sexual relations with other men, which was, in Procopius's narrative, considered an inappropriate forum for persons of standing and was unappreciated by the people of Constantinople. When one of the accusations was ruled as unsubstantiated, Procopius writes that the entire city celebrated.[23]

- ^ According to Procopius, Theodora allegedly declared that Justinian did nothing without her consent in a letter to the Persian ambassador, which the Persian king used to mock the Roman empire stating that no "real state could exist that was governed by a woman."

- ^ Researcher Henning Börm described this social order as a "social hierarchy: people stood over animals, freemen stood over slaves, men stood over eunuchs, and men stood over women. Whenever Procopius denounces the alleged breach of these rules, he is following the rules of historiography."[29]

- ^ While other writers describe the theological battles between the different Christian sects and the government's efforts to manage them, Procopius remains almost silent on these topics.

References

[edit]- ^ Morcillo, Jesús Muñoz; Robertson-von Trotha, Caroline Y. (30 November 2020). Genealogy of Popular Science: From Ancient Ecphrasis to Virtual Reality. Transcript. p. 332. ISBN 978-3-8394-4835-9.

- ^ Hornblower, Simon; Spawforth, Antony; Eidinow, Esther, eds. (2012). The Oxford Classical Dictionary. Oxford University Press. pp. 1214–1215. ISBN 978-0-19-954556-8.

Procopius: Greek historian, born in *Caesarea (2) in Palestine c. AD 500.

- ^ a b Suda pi.2479. See under 'Procopius' on Suda On Line.

- ^ Procopius, Wars of Justinian I.1.1; Suda pi.2479. See under 'Procopius' on Suda On Line.

- ^ Cameron, Averil: Procopius and the Sixth Century, London: Duckworth, 1985, p.7.

- ^ Evans, James A. S.: Procopius. New York: Twayne Publishers, 1972, p. 31.

- ^ Cameron, Procopius and the Sixth Century, p. 6.

- ^ Howard-Johnson, James: 'The Education and Expertise of Procopius'; in Antiquité Tardive 10 (2002), 19–30.

- ^ Börm, Henning (2007) Prokop und die Perser, p.46. Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart. ISBN 978-3-515-09052-0

- ^ Procopius, Wars, 1.12.24.

- ^ Wars, I.18.1-56.

- ^ Wars, I.21.2.

- ^ Wars, I.24.1-58.

- ^ 1.

- ^ Wars, VIII.

- ^ Dolphin, Lambert (16 July 2021). "Visiting the Temple Mount". Temple Mount. Retrieved 18 October 2023.

- ^ Procopius (1914). "Procopius, de Bellis. H.B. (Henry Bronson) Dewing, Ed. [First section:] Procop. Pers. 1.1". Perseus Digital Library. Retrieved 18 October 2023.

[Opening line in Greek] Προκόπιος Καισαρεὺς τοὺς πολέμους ξυνέγραψεν οὓς Ἰουστινιανὸς ὁ Ῥωμαίων βασιλεὺς πρὸς βαρβάρους διήνεγκε τούς τε ἑῴους καὶ ἑσπερίους,... Translation: Procopius from Caesarea wrote the history of the wars of Roman Emperor Justinianus against the barbarians of the East and of the West..

. Greek text edition by Henry Bronson Dewing, 1914. - ^ Börm, Henning. Prokop und die Perser. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, 2007.

- ^ Cresci, Lia Raffaella. "Procopio al confine tra due tradizioni storiografiche". Rivista di Filologia e di Istruzione Classica 129.1 (2001) 61–77.

- ^ Mendelsohn, Daniel (26 December 2010). "God's Librarians". The New Yorker.

- ^ Procopius, Secret History 12.20–22, trans. Atwater.

- ^ Procopius Secret History 9.20–21, trans. Atwater.

- ^ Georgiou, Andriani (2019), Constantinou, Stavroula; Meyer, Mati (eds.), "Empresses in Byzantine Society: Justifiably Angry or Simply Angry?", Emotions and Gender in Byzantine Culture, New Approaches to Byzantine History and Culture, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 123–126, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-96038-8_5, ISBN 978-3-319-96037-1, S2CID 149788509, retrieved 19 December 2022

- ^ Grau, Sergi; Febrer, Oriol (1 August 2020). "Procopius on Theodora: ancient and new biographical patterns". Byzantinische Zeitschrift. 113 (3): 779–780. doi:10.1515/bz-2020-0034. ISSN 1868-9027. S2CID 222004516.

- ^ Evans, James Allan (2002). The Empress Theodora. University of Texas Press. pp. x. doi:10.7560/721050. ISBN 978-0-292-79895-3.

- ^ Cf. Börm (2015).

- ^ Kaldellis, Anthony (2004). Procopius of Caesarea: Tyranny, History, and Philosophy at the End of Antiquity. University of Pennsylvania. pp. 144–147. ISBN 978-0-8122-0241-0. OCLC 956784628.

- ^ Cameron, Averil (1996). Procopius and the sixth century (2nd ed.). London: Routledge. pp. 68–69. ISBN 0-415-14294-6. OCLC 36048226.

- ^ Stewart, Michael Edward (2020). Masculinity, identity, and power politics in the age of Justinian: a study of Procopius. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University. p. 173. ISBN 978-90-485-4025-9. OCLC 1154764213.

- ^ Cameron, Averil (1996). Procopius and the sixth century. London: Routledge. p. 241. ISBN 0-415-14294-6. OCLC 36048226.

- ^ Cameron, Averil (1996). Procopius and the sixth century. London: Routledge. pp. 227–229. ISBN 0-415-14294-6. OCLC 36048226.

- ^ a b Downey, Glanville: "The Composition of Procopius, De Aedificiis", in Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association 78: pp. 171–183; abstract from JSTOR.

- ^ Whitby, Michael: "Procopian Polemics: a review of A. Kaldellis Procopius of Caesarea. Tyranny, History, and Philosophy at the End of Antiquity", in The Classical Review 55 (2006), pp. 648ff.

- ^ Cameron, Averil. Procopius and the Sixth Century. London: Routledge, 1985.

- ^ Croke, Brian and James Crow: "Procopius and Dara", in The Journal of Roman Studies 73 (1983), 143–159.

- ^ Wars, 2.9.14 and 1.7.22.

- ^ Buildings, Book I.

- ^ Whitby, Mary: "Procopius' Buildings Book I: A Panegyrical Perspective", in Antiquité Tardive 8 (2000), 45–57.

- ^ Secret History, 26.18.

- ^ Kaldellis, Anthony (2013). Ethnography after antiquity : foreign lands and peoples in Byzantine literature. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-8122-0840-5. OCLC 859162344.

- ^ de Camp, L. Sprague (1949). Lest Darkness Fall. Ballantine Books. p. 111.

- ^ Melville, Herman (1851). Moby-Dick, or, the Whale. Vol. c.1. London: Harper & Brothers. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.62077.

- This article is based on an earlier version by James Allan Evans, originally posted at Nupedia.

Further reading

[edit]- Adshead, Katherine: Procopius' Poliorcetica: continuities and discontinuities, in: G. Clarke et al. (eds.): Reading the past in late antiquity, Australian National UP, Rushcutters Bay 1990, pp. 93–119

- Alonso-Núñez, J. M.: Jordanes and Procopius on Northern Europe, in: Nottingham Medieval Studies 31 (1987), 1–16.

- Amitay, Ory: Procopius of Caesarea and the Girgashite Diaspora, in: Journal for the Study of the Pseudepigrapha 20 (2011), 257–276.

- Anagnostakis, Ilias: Procopius's dream before the campaign against Libya: a reading of Wars 3.12.1-5, in: C. Angelidi and G. Calofonos (eds.), Dreaming in Byzantium and Beyond, Farnham: Ashgate Publishing 2014, 79–94.

- Bachrach, Bernard S.: Procopius, Agathias and the Frankish Military, in: Speculum 45 (1970), 435–441.

- Bachrach, Bernard S.: Procopius and the chronology of Clovis's reign, in: Viator 1 (1970), 21–32.

- Baldwin, Barry: An Aphorism in Procopius, in: Rheinisches Museum für Philologie 125 (1982), 309–311.

- Baldwin, Barry: Sexual Rhetoric in Procopius, in: Mnemosyne 40 (1987), pp. 150–152

- Belke, Klaus: Prokops De aedificiis, Buch V, zu Kleinasien, in: Antiquité Tardive 8 (2000), 115–125.

- Börm, Henning: Prokop und die Perser. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, 2007. (Review in English by G. Greatrex and Review in English by A. Kaldellis)

- Börm, Henning: Procopius of Caesarea, in Encyclopaedia Iranica Online, New York 2013.

- Börm, Henning: Procopius, his predecessors, and the genesis of the Anecdota: Antimonarchic discourse in late antique historiography, in: H. Börm (ed.): Antimonarchic discourse in Antiquity. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag 2015, 305–346.

- Braund, David: Procopius on the Economy of Lazica, in: The Classical Quarterly 41 (1991), 221–225.

- Brodka, Dariusz: Die Geschichtsphilosophie in der spätantiken Historiographie. Studien zu Prokopios von Kaisareia, Agathias von Myrina und Theophylaktos Simokattes. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, 2004.

- Brodka, Dariusz: Prokop von Caesarea. Hildesheim: Olms 2022.

- Burn, A. R.: Procopius and the island of ghosts, in: English Historical Review 70 (1955), 258–261.

- Cameron, Averil: Procopius and the Sixth Century. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985.

- Cameron, Averil: The scepticism of Procopius, in: Historia 15 (1966), 466–482.

- Colvin, Ian: Reporting Battles and Understanding Campaigns in Procopius and Agathias: Classicising Historians' Use of Archived Documents as Sources, in: A. Sarantis (ed.): War and warfare in late antiquity. Current perspectives, Leiden: Brill 2013, 571–598.

- Cresci, Lia Raffaella: Procopio al confine tra due tradizioni storiografiche, in: Rivista di Filologia e di Istruzione Classica 129 (2001), 61–77.

- Cristini, Marco: Il seguito ostrogoto di Amalafrida: confutazione di Procopio, Bellum Vandalicum 1.8.12, in: Klio 99 (2017), 278–289.

- Cristini, Marco: Totila and the Lucanian Peasants: Procop. Goth. 3.22.20, in: Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies 61 (2021), 73–84.

- Croke, Brian and James Crow: Procopius and Dara, in: The Journal of Roman Studies 73 (1983), 143–159.

- Downey, Glanville: The Composition of Procopius, De Aedificiis, in: Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association 78 (1947), 171–183.

- Evans, James A. S.: Justinian and the Historian Procopius, in: Greece & Rome 17 (1970), 218–223.

- Evans, James A. S.: Procopius. New York: Twayne Publishers, 1972.

- Gordon, C. D.: Procopius and Justinian's Financial Policies, in: Phoenix 13 (1959), 23–30.

- Greatrex, Geoffrey: Procopius and the Persian Wars, D.Phil. thesis, Oxford, 1994.

- Greatrex, Geoffrey: The dates of Procopius' works, in: BMGS 18 (1994), 101–114.

- Greatrex, Geoffrey: The Composition of Procopius' Persian Wars and John the Cappadocian, in: Prudentia 27 (1995), 1–13.

- Greatrex, Geoffrey: Rome and Persia at War, 502–532. London: Francis Cairns, 1998.

- Greatrex, Geoffrey: Recent work on Procopius and the composition of Wars VIII, in: BMGS 27 (2003), 45–67.

- Greatrex, Geoffrey: Perceptions of Procopius in Recent Scholarship, in: Histos 8 (2014), 76–121 and 121a–e (addenda).

- Greatrex, Geoffrey: Procopius of Caesarea: The Persian Wars. A Historical Commentary. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2022.

- Howard-Johnson, James: The Education and Expertise of Procopius, in: Antiquité Tardive 10 (2002), 19–30

- Kaçar, Turhan: "Procopius in Turkey", Histos Supplement 9 (2019) 19.1–8.

- Kaegi, Walter: Procopius the military historian, in: Byzantinische Forschungen. 15, 1990, ISSN 0167-5346, 53–85 (online (PDF; 989 KB)).

- Kaldellis, Anthony: Classicism, Barbarism, and Warfare: Prokopios and the Conservative Reaction to Later Roman Military Policy, American Journal of Ancient History, n.s. 3-4 (2004-2005 [2007]), 189–218.

- Kaldellis, Anthony: Identifying Dissident Circles in Sixth-Century Byzantium: The Friendship of Prokopios and Ioannes Lydos, Florilegium, Vol. 21 (2004), 1–17.

- Kaldellis, Anthony: Procopius of Caesarea: Tyranny, History and Philosophy at the End of Antiquity. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004.

- Kaldellis, Anthony: Prokopios’ Persian War: A Thematic and Literary Analysis, in: R. Macrides, ed., History as Literature in Byzantium, Aldershot: Ashgate, 2010, 253–273.

- Kaldellis, Anthony: Prokopios’ Vandal War: Thematic Trajectories and Hidden Transcripts, in: S. T. Stevens & J. Conant, eds., North Africa under Byzantium and Early Islam, Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks, 2016, 13–21.

- Kaldellis, Anthony: The Date and Structure of Prokopios’ Secret History and his Projected Work on Church History, in: Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies, Vol. 49 (2009), 585–616.

- Kovács, Tamás: "Procopius's Sibyl - the fall of Vitigis and the Ostrogoths", Graeco-Latina Brunensia 24.2 (2019), 113–124.

- Kruse, Marion: The Speech of the Armenians in Procopius: Justinian's Foreign Policy and the Transition between Books 1 and 2 of the Wars, in: The Classical Quarterly 63 (2013), 866–881.

- Lillington-Martin, Christopher, 2007–2017:

- 2007, "Archaeological and Ancient Literary Evidence for a Battle near Dara Gap, Turkey, AD 530: Topography, Texts and Trenches" in BAR –S1717, 2007 The Late Roman Army in the Near East from Diocletian to the Arab Conquest Proceedings of a colloquium held at Potenza, Acerenza and Matera, Italy edited by Ariel S. Lewin and Pietrina Pellegrini, pp. 299–311;

- 2009, "Procopius, Belisarius and the Goths" in Journal of the Oxford University History Society,(2009) Odd Alliances edited by Heather Ellis and Graciela Iglesias Rogers. ISSN 1742-917X, pages 1– 17, https://sites.google.com/site/jouhsinfo/issue7specialissueforinternetexplorer Archived 2022-06-30 at the Wayback Machine;

- 2011, "Secret Histories", http://classicsconfidential.co.uk/2011/11/19/secret-histories/;

- 2012, "Hard and Soft Power on the Eastern Frontier: a Roman Fortlet between Dara and Nisibis, Mesopotamia, Turkey: Prokopios’ Mindouos?" in The Byzantinist, edited by Douglas Whalin, Issue 2 (2012), pp. 4–5, http://oxfordbyzantinesociety.files.wordpress.com/2012/06/obsnews2012final.pdf;

- 2013, Procopius on the struggle for Dara and Rome, in A. Sarantis, N. Christie (eds.): War and Warfare in Late Antiquity: Current Perspectives (Late Antique Archaeology 8.1–8.2 2010–11), Leiden: Brill 2013, pp. 599–630, ISBN 978-90-04-25257-8;

- 2013 “La defensa de Roma por Belisario” in: Justiniano I el Grande (Desperta Ferro) edited by Alberto Pérez Rubio, no. 18 (July 2013), pages 40–45, ISSN 2171-9276;

- 2017, Procopius of Caesarea: Literary and Historical Interpretations (editor), Routledge (July 2017), www.routledge.com/9781472466044;

- 2017, "Introduction" and chapter 10, “Procopius, πάρεδρος / quaestor, Codex Justinianus, I.27 and Belisarius’ strategy in the Mediterranean” in Procopius of Caesarea: Literary and Historical Interpretations above.

- Maas, Michael Robert: Strabo and Procopius: Classical Geography for a Christian Empire, in H. Amirav et al. (eds.): From Rome to Constantinople. Studies in Honour of Averil Cameron, Leuven: Peeters, 2007, 67–84.

- Martindale, John: The Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire III, Cambridge 1992, 1060–1066.

- Max, Gerald E., "Procopius' Portrait of the (Western Roman) Emperor Majorian: History and Historiography," Byzantinische Zeitschrift, Sonderdruck Aus Band 74/1981, pp. 1-6.

- Meier, Mischa: Prokop, Agathias, die Pest und das ′Ende′ der antiken Historiographie, in Historische Zeitschrift 278 (2004), 281–310.

- Meier, Mischa and Federico Montinaro (eds.): A Companion to Procopius of Caesarea. Brill, Leiden 2022, ISBN 978-3-89781-215-4.

- Pazdernik, Charles F.: Xenophon’s Hellenica in Procopius’ Wars: Pharnabazus and Belisarius, in: Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies 46 (2006) 175–206.

- Rance, Philip: Narses and the Battle of Taginae (552 AD): Procopius and Sixth-Century Warfare, in: Historia. Zeitschrift für alte Geschichte 30.4 (2005) 424–472.

- Rubin, Berthold: Prokopios, in Realencyclopädie der Classischen Altertumswissenschaft 23/1 (1957), 273–599. Earlier published (with index) as Prokopios von Kaisareia, Stuttgart: Druckenmüller, 1954.

- Stewart, Michael, Contests of Andreia in Procopius’ Gothic Wars, Παρεκβολαι 4 (2014), pp. 21–54.

- Stewart, Michael, The Andreios Eunuch-Commander Narses: Sign of a Decoupling of martial Virtues and Hegemonic Masculinity in the early Byzantine Empire?, Cerae 2 (2015), pp. 1–25.

- Stewart, Michael, Masculinity, Identity, and Power Politics in the Age of Justinian: A Study of Procopius, Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2020:https://www.aup.nl/en/book/9789462988231/masculinity-identity-and-power-politics-in-the-age-of-justinian

- Treadgold, Warren: The Early Byzantine Historians, Basingstoke: Macmillan 2007, 176–226.

- The Secret History of Art by Noah Charney on the Vatican Library and Procopius. An article by art historian Noah Charney about the Vatican Library and its famous manuscript, Historia Arcana by Procopius.

- Whately, Conor, Battles and Generals: Combat, Culture, and Didacticism in Procopius' Wars. Leiden, 2016.

- Whitby, L. M. "Procopius and the Development of Roman Defences in Upper Mesopotamia", in P. Freeman and D. Kennedy (ed.), The Defence of the Roman and Byzantine East, Oxford, 1986, 717–35.

External links

[edit]Texts of Procopius

[edit]- Works by Procopius in eBook form at Standard Ebooks

- Works by Procopius at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Procopius at the Internet Archive

- Works by Procopius at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Complete Works, Greek text (Migne Patrologia Graeca) with analytical indexes

- The Secret History, English translation (Atwater, 1927) at the Internet Medieval Sourcebook

- The Secret History, English translation (Dewing, 1935) at LacusCurtius

- The Buildings, English translation (Dewing, 1935) at LacusCurtius

- The Buildings, Book IV Greek text with commentaries, index nominum, etc. at Sorin Olteanu's LTDM Project

- H. B. Dewing's Loeb edition of the works of Procopius: vols. I–VI at the Internet Archive (History of the Wars, Secret History)

- Palestine Pilgrims' Text Society (1888): Of the buildings of Justinian by Procopius, (ca 560 A.D)

- Complete Works 1, Greek ed. by K. W. Dindorf, Latin trans. by Claude Maltret in Corpus Scriptorum Historiae Byzantinae Pars II Vol. 1, 1833. (Persian Wars I–II, Vandal Wars I–II)

- Complete Works 2, Greek ed. by K. W. Dindorf, Latin trans. by Claude Maltret in Corpus Scriptorum Historiae Byzantinae Pars II Vol. 2, 1833. (Gothic Wars I–IV)

- Complete Works 3, Greek ed. by K. W. Dindorf, Latin trans. by Claude Maltret in Corpus Scriptorum Historiae Byzantinae Pars II Vol. 3, 1838. (Secret History, Buildings of Justinian)

Secondary material

[edit]- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Entry for Procopius from the Suda.